I am perhaps a bit lost on the argument that states there is never a place for discussing how a program is designed to be used, and how workflows can be adopted within that optimal framework. That seems a fairly basic topic of conversation that might come up from time to time in just about any program of moderate flexibility and sophistication, particularly if there is a problem being encountered which has come about through using the program at a high level of friction, counter to its design—and particularly in a program that approaches several problems from a fairly unorthodox position.

Say for example you encounter someone on a Photoshop board that is struggling to get some elaborate macro to work which describes a process they have “always used in every other program”. You take one look at what they are doing and see they have never before encountered the concept of a layer.

Do you stand back and say: good for you, keep struggling with that one single layer. Or do you say, hey, this program is designed around the notion of layers, and here is how they can make your life so much easier. Maybe they’ll come back and say, “MS Paint has been doing things this way since the '90s, surely that means there is some merit…”.

Is one right while the other is wrong? No, of course not, I would view very few usage patterns in software in such black and white terms, but it would be folly to suggest that friction does not exist, and that all paths are equally seamless throughout any program—particularly programs with a strong idea in their design.

Inversely, we could try to apply Scrivener’s model to something like a typical Markdown editor, even one that has an efficient inter-document navigation system built into it, and see that breaking down a long text into individual files by heading structure and even deeper would run into problems of friction—because the software isn’t designed for that approach. Instead it has a bounty of tools for internal navigation within larger chunks of text.

The same is true for how most word processors are optimised and designed to be used. Trying to use LibreOffice to the degree I use Scrivener’s outline model at a file system level would be an utter nightmare: thousands upon thousands of paragraph-length .odt files. I would be using LibreOffice at a high level of friction, and if someone on a forum saw me struggling with trying to manage that mess they would hopefully rightly point out that the program is designed to work a different way, and that I’ll have a much easier time if work in 10k word chunks, and use the master document feature, or transclusion in Markdown-based tools.

Am I using it wrongly? Perhaps not, nothing is breaking, but am I working in a way that conflicts with the software’s design model? You bet!

Now this goes beyond what we interface with as users, in the visible feature set, too. A program that is designed to work with long, let’s say 50k word documents, is going to have different programming challenges in its design. It’s going to need memory management to handle having so much data in one single view, it’s going to need to use threading to fork potentially lengthy resource-intensive processes into the background while you work, such as auto-save and pagination.

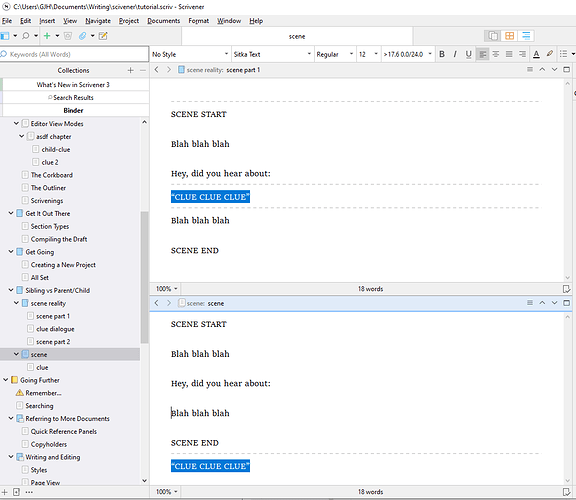

In a program not designed for that, it would face different challenges, and probably would not waste development time solving programs it wouldn’t encounter. For example, a programming challenge we face with Scrivener’s design that hardly any word processor has to deal with is what happens when you click on a 2,000 outline node root outline item and tell the software to edit it as a single linear text. From there it must branch out through the file system and build a seamless editing environment from potentially up to 6,000 individual files on your disk, literal files, that are all assembled into various features within the software to provide you with this view mode. Can you imagine what would happen if you selected six thousand DOCX files and instructed Word to load all of them at once? Your swap disk would have a fun time with that.

Different challenges! Different places to put your coding effort.

Someone might put 180,000 words into a Scrivener outline node and wonder why it gets sluggish for example, why it halts and blocks input periodically (our simpler block-input auto-save system which is optimised for short packets of information into multiple files on the disk). Simply put, we’ve not spent years of development effort building efficient single-view editing environment because that’s not how it is designed to be used—but distribute that 180k over many documents, and it thrives.

This is kind of design stuff that goes into software, and intentionally working against that design will cause friction as well. Would you rather nobody told you about it?

The very manner in which the comment window is designed seems built for the need to click and jump precisely to each one.

I can see how that might seem that way to you on the surface, but it’s worth bearing in mind that this model is designed to span across “document” boundaries when working with larger texts in Scrivenings mode. Its feature set does indeed work on a single longer document, but that’s not why it has that feature set—it has that feature set so you can assemble Chapter 21 out of its 120 individual outline nodes in a linear fashion, and jump from one comment to the next, regardless of where it comes from on the disk.

It’s also worth bearing in mind that Scrivener used to have an internal bookmarking mechanism that was in fact removed from the software precisely because it was bloat. It was contradicting the design goal of having an articulated outline-based text, by having a mechanism that encouraged long unarticulated sections instead.

To be clear, you cannot put the child text at a spot of your choosing, it’s literally just parent first, then child 1, child2, ect. Those are three siblings, and this disconnect is the root of this, and likely other problems.

I may not entirely understand the concerns with this model. I do in fact come from a background of writing in outliners as opposed to document editors (which I’ve always felt out of sorts in), so what you’re describing—this linear relationship between nested nodes, to me feels entirely normal and expected. I don’t see what is wrong with that.

I think I understand what you are getting at, that you feel an outline shouldn’t represent the actual flow of the text literally, and that it should instead represent peaks that we mark out in a longer text? I would start by saying that’s not a traditional outline—that’s more like a word processor’s navigator tool, where various objects in the document becomes navigational peaks—that’s fine and good, but it’s not a model that the outline itself would work upon. Such things might arise in the feature set, for example in an org-mode outline we might use an agenda view that extracts peaks from the outline in the form of dated tasks—we can do similarly in Scrivener by pulling out outline nodes into a separate list, either dynamically as a search result or by building our own curated lists. But these kinds of supra-outline features are not part of the outline model itself, which you seem to be suggesting they should be.

That said, I think to a degree Scrivener does indeed do what you’re looking for. Let’s say for example you want all of your figures and tables to be in separate outline nodes for the sake of being able to refer to them specifically, and to create lists of them easily, and so on. Nobody would argue with the usefulness of having a list of figures. At the same time you don’t want to chop up a small subsection into three parts purely for the sake of having a discrete image object in the outline. This quandary is what I referred to above as breaking things down for purely mechanical reasons, and why that is often not desirable and ultimately can counteract the intended design by flooding what should be a concise human-friendly outline with mechanical artefacts of the document design.

So you go to the spot where you want to insert the figure in the text, you type in <$include>, select it, and hit ⌘L / Ctrl+L to link to a new document. You designate its name and location and it opens up in the second split. You drop your image into the other editor, maybe throw in a caption, and close it.

There you go: now you have a discrete outline object (which could be stored in an appendix folder with a special section type override that prints each caption instead of the image in a list of links back to the figures), that is embedded into an atomically concise text that isn’t broken apart just to accommodate that object. If you want to see that object, you click the link. It’s kind of like what you’re describing—if I understand correctly. Again, what you seem to be describing isn’t how any outline I’ve ever used works, so I may be off on that.

In this specific case, Scrivener is not “achieving its vision” or whatever, the missing feature is why people need to hack together their workarounds.

None of my working methods above are “workarounds” or “hacks”. They are logical extensions of the feature set that work efficiently within its design, and for the most part they are all doing what the design was built to make possible and efficient (funnily enough).

Perhaps you are using these words in a less technical sense than I would, however. A workaround, by definition, has a specific meaning that pertains to bugs and issues that implies a temporary bridge over a blocking problem that allows you to continue working until it is fixed.

I would close by again reiterating that the primary problem with granular hyperlinking is a lack of technology to build it in a feasible time-frame. All of the above, whether the model of the software depends this technique less than a model that must work in longer chunks of text, etc., is somewhat beside that point. Or another way of putting it, I would say that the lack of granular linking isn’t an ideological choice and that having such a feature probably would be beneficial even within its framework. We can say both things at once: that a program doesn’t need something as much as another might (like a web page), while at the same time stating it could benefit, but likely never will on account of technical limitations.