Screenshot update | 2025-01-20

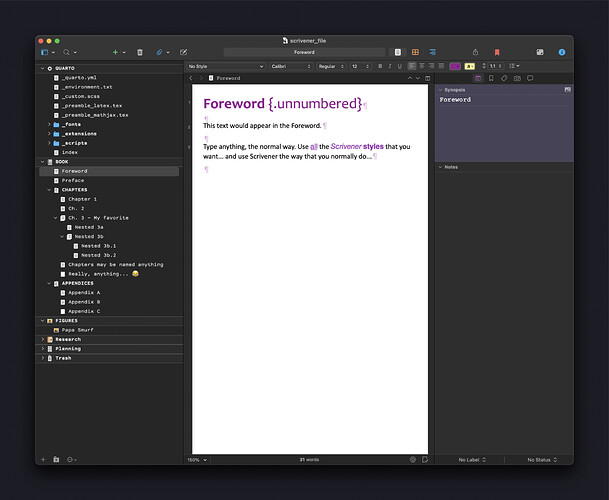

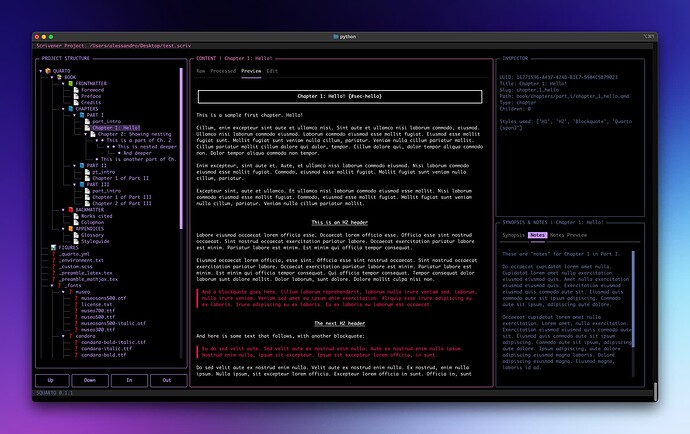

For anybody interested, here is how Squarto is set up to facilitate creation of a Quarto Book project. All writing takes place in Scrivener, using all the normal tools (like the binder, styles, etc.). The Squarto template for Scrivener gives a good starting point for structure of the binder.

Zooming in on the binder, there are sections for Quarto files, the book itself (including front matter, parts/chapters, and appendices), and figures.

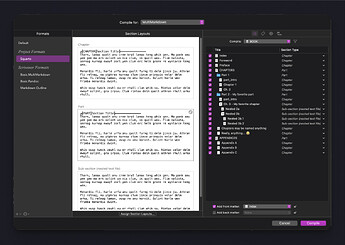

Building the Quarto Book is initiated through Scrivener’s Compile command. The Squarto template for Scrivener has built-in section layouts to auto-assign the structure of the binder.

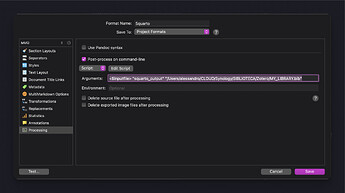

The Squarto compile format includes a processing step that will pass important arguments, such as where the COMPILED_BY_SCRIVENER.md output file is located, what you want to name the root directory for the Quarto book (in this case, squarto_output), and where your references .bib file is located (which will be included in the project as a copy or as an alias).

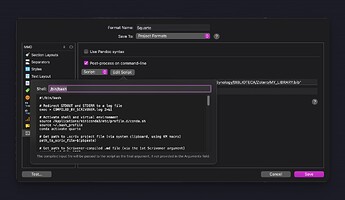

Of course, most of the processing itself is done via the embedded bash script.

There are some pretty cool features in the bash script, such as redirecting STDOUT and STDERR to a log file, pasting the path to the .scriv project file (since Scrivener doesn’t have a native way to pass this path to the Compile step, as detailed in this thread), prepending key parameters into the COMPILED_BY_SCRIVENER.md document for later reference, and finally, executing squarto build at the command line. The script is executed in a virtual environment (in my case, using conda).

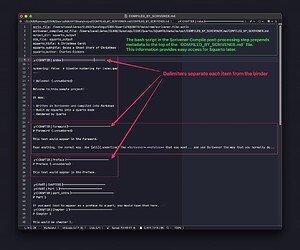

The post-processed COMPILED_BY_SCRIVENER.md looks something like this:

The top section contains prepended metadata that will be used by Squarto later. Each item from the binder is separated by a delimiter (that Scrivener adds via the Section Type and Section Layout functionality). Squarto uses this later to parse the sections of the compiled text and save the content into separate files, ordered hierarchically within the Quarto Book project, as was visually laid out within the binder.

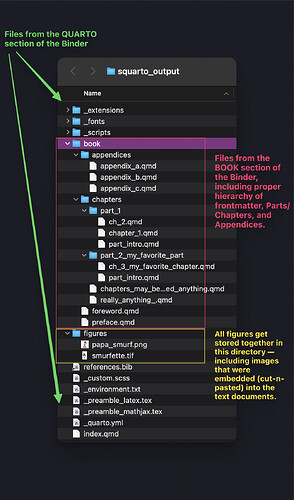

The Quarto Book project is created on the filesystem as a hierarchy of folders and files. Text documents within the Scrivener ‘DraftFolder’ were parsed from the COMPILED_BY_SCRIVENER.md file and then stored in the appropriate location. (Quarto uses the .qmd extension for Quarto Markdown format.) Other files (e.g., _quarto.yml, fonts and scripts, and images) are copied from the deep internal recesses of the .scriv project package into the proper location. You might notice that the filenames for the text documents are “slugified” versions of the titles in the binder. Emojis are removed ![]() lol.

lol.

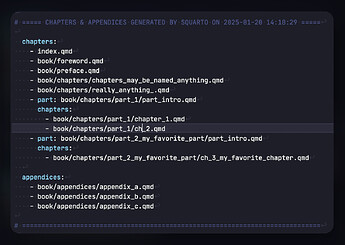

A Quarto Book requires a properly formatted _quarto.yml configuration file to tell Quarto what to do. This file is dynamically created by Squarto to show the correct paths to all the parts, chapters, and appendices. You don’t have to edit this portion of _quarto.yml yourself – all you do is rearrange/rename things in the Binder, and the YAML is auto-generated at Compile/post-process time!

With the Quarto Book project properly saved in all its bits-n-pieces, it is now ready for rendering using quarto render into whatever format you want (e.g., PDF), or quarto preview for a preview in the browser.

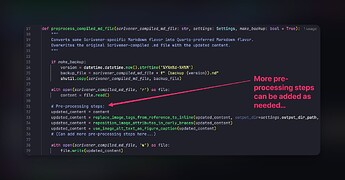

Of course, there are tons more details about the internals of the project. I continue to refactor it to make it more robust against edge cases. And I continue to work on the Squarto Scrivener project template itself, in which all the styles and compile settings are defined. Squarto is quite modular and extensible now, so I can continue to develop pipeline steps that are relatively easy to add – for example, pre-processing steps that I want to run on the COMPILED_BY_SCRIVENER.md file before parsing and saving the content to files. For example, this is how I correct image tag attributes.

I’m now at the point where I can use Squarto in “real life” (with “real projects”); that said, it’s still beta software, and I continue to improve it. Let me know what questions/suggestions you have about it!

Many thanks to @nontroppo, @AmberV, @kewms, @KB, and others for the great tips along the way.