Something I think that is fallen by the wayside in this discussion is that it has revolved entirely around the notion that without this thing Scrivener is deficient, and whether or not that is the case, as opposed to what Scrivener offers instead.

To expand on something I’ve said in the original post, and again in a follow-up above, is that is I feel there are strong advantages to the methods described here that anchor & link systems have strong weaknesses with. I don’t think it is quite so clear cut as to say that one is definitely better than the other. I would even go so far as to say that the mechanisms we can use in Scrivener are probably better for writers than the anchor & link system, which is probably better for readers (the web page example again).

The kind of difference I’m speaking of here is similar I think to the differences in footnotes in a book, and footnotes in software. The way Scrivener handles footnotes is to my mind a superior model for writers in just about every way (other than perhaps visualising what the reader will interface with). Presenting footnotes in a manner that is best for readers in software has always struck me as awkward, particularly in page layout programs where the tendency is to make the physical page larger than the screen to overcome disparity in print quality. To write a footnote you’re taken off to another part of the screen, losing your context, and likewise have to jump around to read it later on. A footnote in a sidebar on the other hand is right there, readily available, and having an overview of all the footnotes relevant to the region of text you’re working on, stacked regardless of their actual distance in the text, is extremely valuable. This contextual pairing is even stronger with inline footnotes, which some prefer to use for that very reason. Your notation and what you are notating are immediately adjacent.

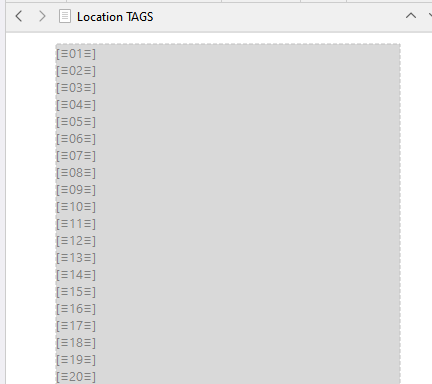

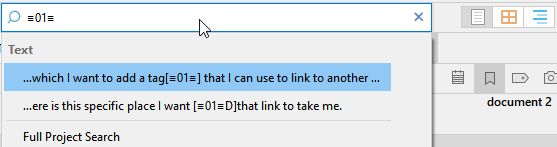

Where it comes to mechanisms that promote rapid navigation between textual markers we encounter clustering capabilities, bi-directionality, direction-less (or anticipation-based marking) and egalitarian marker importance that together create for a content-creation focussed environment. I can at a simple flick of my wrist assemble a list of all instances of a marker throughout hundreds of pages of text, jump to any one of them and remove it without fear of harming the rest of the cluster. There is no root anchor I must be careful around, that all satellite links depend upon for functioning, they are all root anchors until the last one is deleted. This elevates the concept of binding text fragments together into workflows rather than purely as end point to root point navigation mechanisms.

There are other operational advantages as well. I feel an invisible anchor mark in the text is less useful than a descriptive one. I don’t like how a hyperlink cannot be readily annotated for its purpose in linking somewhere. Sometimes a tooltip can tell us where we are going, but rarely why, and not without heaps of UI in the way in order to define that why. And the heaps of UI is certainly something to consider as well. The amount of clicking through panels and buttons in order to make an anchor & link in a typical word processor is far from efficient, whereas the mechanisms we have in Scrivener are just like typing. There is very little operational difference in binding two pieces of disparate text together as there is in typing.

To me, the way word processors handle this matter doesn’t feel like a writing tool—and I really don’t think it is. It’s a reader tool, like the footnote, that writers have historically used for their own purposes which, as I noted before, must be dismantled by hand before publication—because it is a reader tool.

The other argument is that one requires an “intricate” or complex system, which implies the other does not. To me that seems less an intrinsic necessity in any system or approach that targets a specific spot, and more a product of how frequently or extensively one uses it. You can have an intricate system using hyperlinks with point-to-point anchor points, and you can have an intricate system using markers. Both could also be used fairly simply, as well.

Perhaps a comparison of the two methods would better show how I do feel the marker approach is generally the most efficient approach to solving that specific problem, in a way that requires less technological overhead and manual labour, and meanwhile offers levels of flexibility that no single-direction linkage system provides—and thus with these considerable and unique advantages, hardly deserving of the phrase “workaround”.

Disclaimer: I am not by any means a word processing expert. I could be missing some really crucial details in here that would make some of the cons a bit less so.

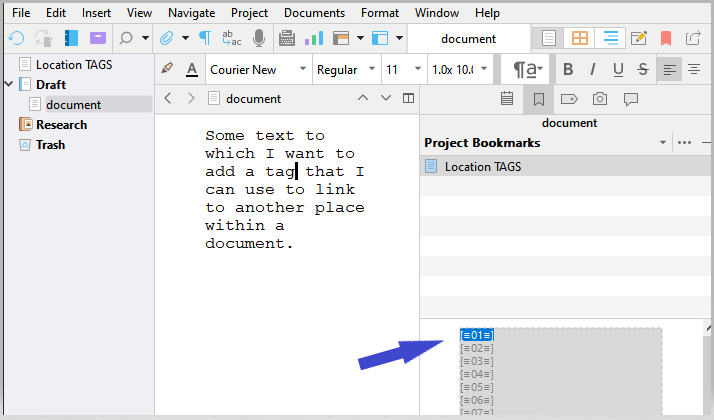

Adding an Anchor Point

In Scrivener:

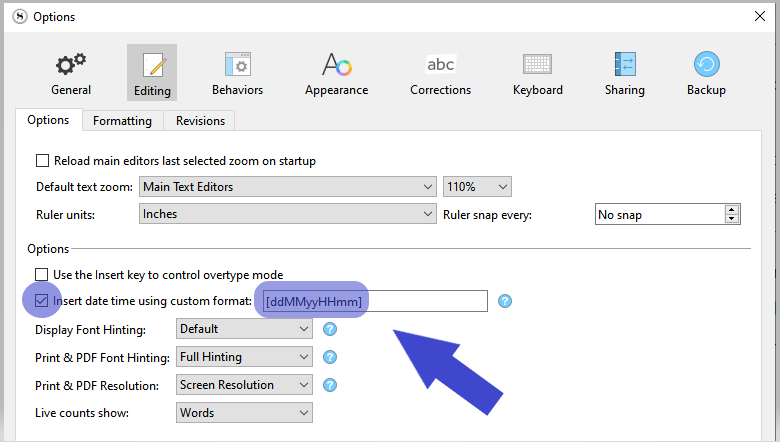

Insert ▸ Inline Annotation-

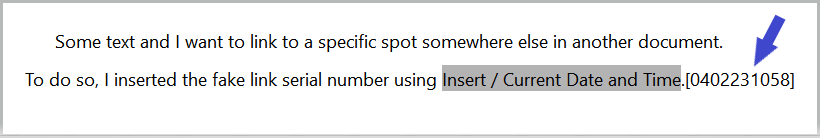

Insert ▸ Current Date & Time (again I’ll just stick with that for simplicity, it is not a dependency).

Result: an obvious marker, easy to locate while scrolling around if that’s beneficial, and a “mindless” approach to generating anchor identity. A characteristic of this approach is that the opportunity for explanation of the link’s purpose is readily available. While we may not often need it, jotting down why we created an anchor in the first place is second-nature, and can be done immediately after step two by simply continuing to type. We can stop commenting by using the same exact shortcut we used to start adding the marker—and keep writing.

In LibreOffice:

- Use the

Insert/Bookmark... menu command.

- Come up with and type out a unique marker ID.

- Click the

Insert button.

Not a lot more in terms of raw manual labour, but when you look at the sort of mechanical and mental properties involved, there is more going on than seems at first blush. You have to come up with unique identifiers yourself somehow. Maybe you can use date as well, but that will make things difficult for you later, and not everyone has a handy universal way to insert dates everywhere. On a mechanical level there is a lot more mousing around by having to click on buttons in a GUI.

Result: an invisible marking in the document you’ll never stumble across without using sidebar navigation. Everything that must be known about this link needs to be communicated through the marker ID itself. There is little opportunity for annotation without invoking additional commands and inserting more formatting that must be removed later.

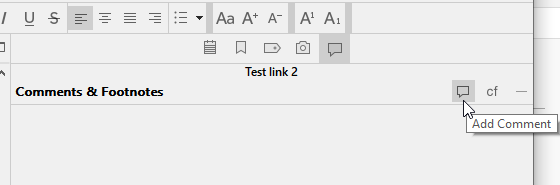

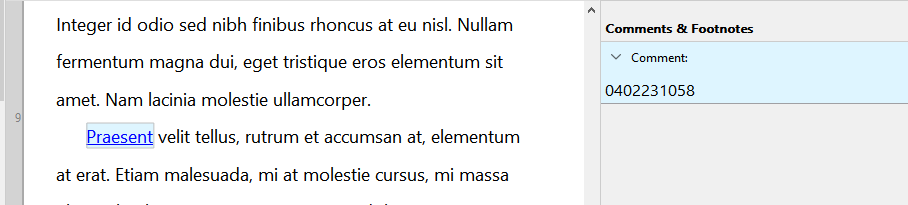

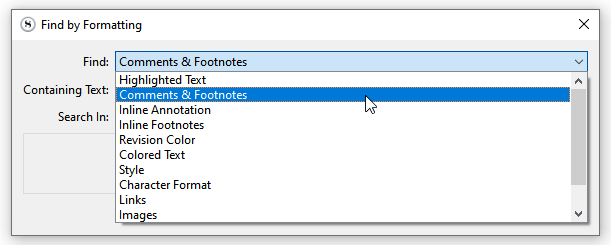

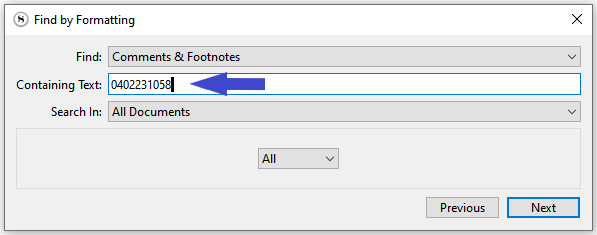

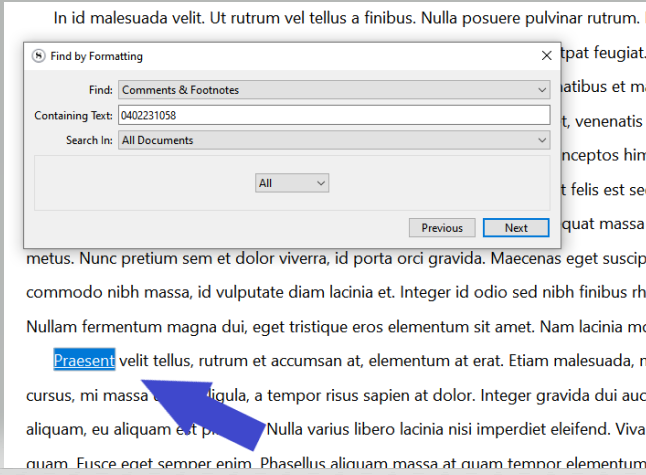

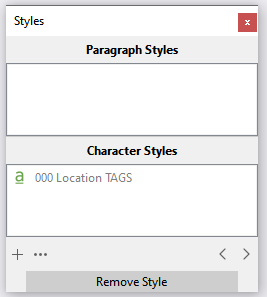

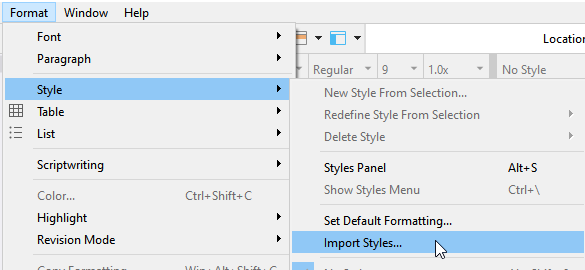

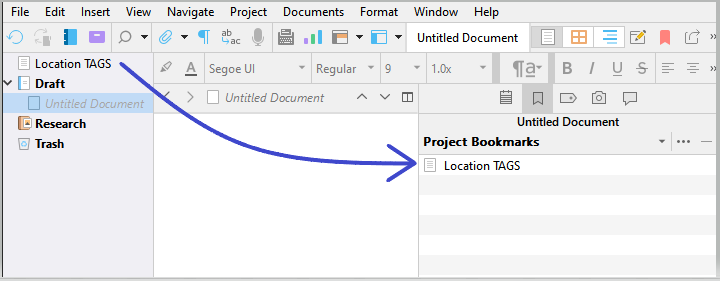

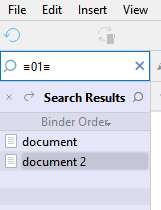

Scrivener variation: now, you might be thinking that the sidebar is actually a benefit of this approach that Scrivener does not have—but that is not in fact the case, and can be achieved with a simple adjustment to step (1): use an inspector comment instead—now you have it in a list. It’s not my preference, I prefer the seamless notate-while-writing that inlines give you, but if a sidebar for jumping to markers is vital to you, that’s an easy option.

Conclusion: since using lists of anchors with “mindless” anchor names is a universal problem, you’ll probably want to adopt the higher mental cost on the creation of each bookmark, giving them descriptive names—but if a navigable list is important to you anyway, then it is worth the cost. The datestamp approach has clear advantages for, as put above, quick and often times temporary links between two portions of text, whereas the uniquely named marker approach is better for intricate systems of cross-referenced markers. These are choices rather than requirements of any particular approach, in other words.

Linking to the Anchor

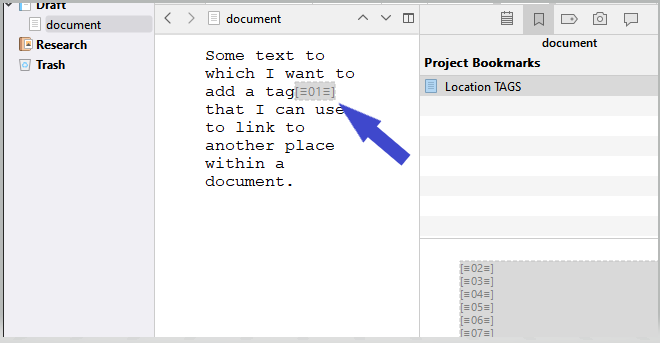

In Scrivener:

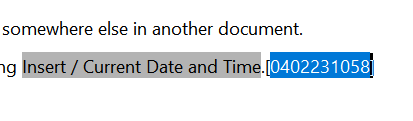

Edit/Select/Select Annotation-

⌘C / Ctrl+C (copy)

- Click into the place where you want to refer from and press

⌘V / Ctrl+V to paste. Here I’m assuming a split view workflow where both texts are scrolled into view.

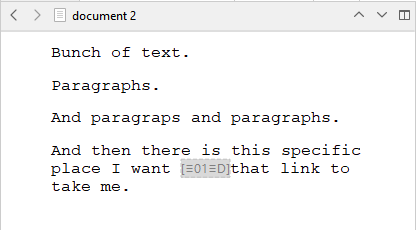

Result: we now have a symmetrical linkage between these two points in the text. Both instances of the annotated date-stamp (or descriptive anchor, as you wish) have the same characteristics and method toward discovering the matching anchor.

In LibreOffice:

Steps...

- Select the text in the editor to create a hyperlink from.

- Use the

Insert/Cross-Reference... menu command to bring up the Fields dialogue.

- Select the “Bookmarks” type, in the upper-left area.

- Locate and select the anchor point you’ve created (here is where using dates alone would grow unworkable).

- In the lower left corner, select the manner in which the reference should be printed in the editor. For our purposes, this is somewhat arbitrary, but it is still something one must do, each and every time.

- Click the

Insert button.

- Click the

Close button.

Result: similarly to an inline annotation, we get a form of “meta text” inserted into the text flow. The actual identity of what we’re linking to is likely obscured. The only way to know before clicking the link is to reach for the mouse and position the pointer carefully over the highlighted area, and then wait for a second or two, until a tooltip appears. Not exact a good tool for skimming quickly and locating connectivity by eye.

LibreOffice variation: you may be thinking that I’m off on the wrong track, and that you meant a simple hyperlink rather than a cross-reference. I’m aware of that approach as well, but the workflow is not substantially less labour-intensive:

Steps...

- Select the text in the editor to create a hyperlink from.

-

⌘K (insert hyperlink)

- Click on the “Document” button along the left list.

- Within the “Target in Document” section, click the target button to the right of the text field.

- Locate and select the anchor point you’ve created.

- Click the

Apply button in the secondary pop-up.

- Click the

OK button in the primary dialogue.

A bit less complex and laden with superfluous options, though I still would not consider that to be very user-friendly at scale (scrolling through a large list of bookmarks in that little pop-up for instance, sounds like the sort of thing that would drive one to other methods).

Conclusion: even with the slightly more straight-forward concept as the product, the actual result that we get still requires over half a dozen different actions from the user. The relationship we’ve established in the document between these points is very one-directional. We can travel to an anchor point from the link, but at the invisible marker where the anchor exists, there is no indication of what links to this spot, and no way to get back to those spot(s). So it is a decidedly asymmetrical linkage, unlike Scrivener’s—and as far as I know, the same goes for cross-references.

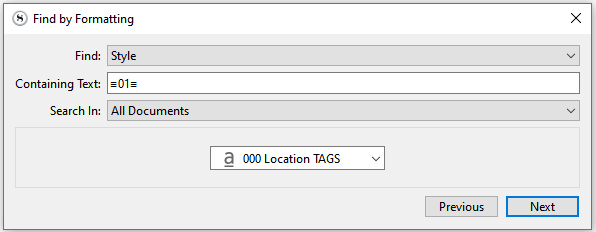

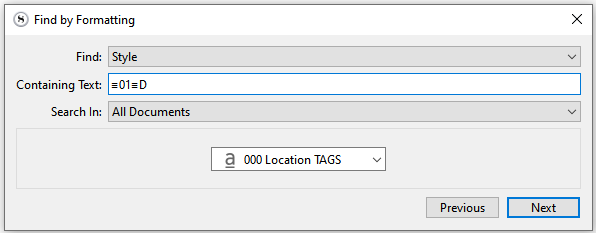

Linking to No Anchor

What’s this about? Well you don’t always know that you need to link to a place while you’re looking right at that place. In fact, for how I work anyway, I tend to realise I need to link to a spot elsewhere in the project, rather than coming across a spot and realising there is a spot elsewhere that should link here where I’m already working. The above examples all presumed we had the target in view, but what happens when we don’t?

In Scrivener:

Steps...

Insert ▸ Inline AnnotationInsert ▸ Current Date & TimeEdit/Select/Select Annotation-

⌘C / Ctrl+C (copy)

- Navigate (using whatever method you prefer) to place where you want to refer to and press

⌘V / Ctrl+V to paste.

-

⌘[ / Ctrl+[ to return to where you were previously typing.

Of course, if you go back and compare the two checklists, that’s exactly the same list of steps! This is another facet of what is meant by having a symmetrical linkage between texts. It doesn’t only refer to the utility of the product, but a reduction in the complexity of the creation of that product. Where there is no cognitive difference between anchor and link, there is no mental burden in organising the information flow within a document. We do not have to select between two directional tools, we always do the same thing.

This is what I mean by having a “mindless” editing process. With our mind not encumbered by the particulars of establishing a directional linking system—having to come up with unique and descriptive anchor names, having to think in terms of link vs anchor, etc.—we can focus more purely upon the work itself, rather than the technology supporting it.

Content creation, not building a system for readers.

In LibreOffice:

Now here is where things get problematic. We’re at a point in the document where we’ve realised we want to link from this spot to another that is off-screen. If we simply go straight to that spot and proceed with the anchor point checklist, we’ve lost our place! So how do we solve that problem? I suppose one way would be to use the very technology that we need to create a link—it is a bookmark after all. So:

Steps...

- Use the

Insert/Bookmark... menu command.

- Come up with an type out a unique marker ID, maybe “RETURN POINT”.

- Click the

Insert button.

- Great, now we’re off and scrolling around to find the target spot. Once we get there:

- Use the

Insert/Bookmark... menu command.

- Come up with an type out a unique marker ID.

- Click the

Insert button.

- Use

F5 to load the Navigator.

- Locate the “RETURN POINT” bookmark and double-click on it to activate the bookmark.

- Press

Delete to remove it.

- Close the Navigator window. And now we start in with the process of creating a hyperlink or cross-reference to the bookmark we just jaunted to and from. I’ll just pick one arbitrarily as they both seem to be about the same in terms of checklist load:

- Select the text in the editor to create a hyperlink from.

-

⌘K (insert hyperlink)

- Click on the “Document” button along the left list.

- Within the “Target in Document” section, click the target button to the right of the text field.

- Locate and select the anchor point you’ve created.

- Click the

Apply button in the secondary pop-up.

- Click the

OK button in the primary dialogue.

You might argue that I’m getting pedantic by spelling out each and every step one must take to create a link, from anywhere in the text, but I do think it is important, when examining two different approaches for their relative efficiency and utility, to go over all common contingencies in their usage. The first checklists looked at the two processes from the link’s most efficient context: where we have the intended anchor point directly in view. But like I say, we can’t assume that will always be the case, or even often the case. For myself, the above eighteen (!!) point checklist is often what would be necessary.

LibreOffice variant: while we’re looking at this facet of usage, I think it’s a good place to note that this checklist is roughly how one would achieve a form of symmetry in the traditional directional hyperlink model. We would only need to tweak this checklist in two places: first coming up with a stable and better unique ID for the starting point, and secondly, instead of deleting the anchor point once we return, inserting another seven-point checklist after step (4) to link to the first anchor we created, before returning and then linking to the second anchor.

So while the utility of having symmetrical linkages may seem appealing to emulate in a hyperlink model, once one sees their power and low mental overhead in action in Scrivener—I’m really not sure if it is worth the twenty-point checklist in order to achieve them, and the mental overhead advantages only exist within the product rather than in the creation of it.

Link Activation

Finally we get to the point where there can be said to be a clear advantage to the hyperlink approach.

In Scrivener:

Edit/Select/Select Annotation-

⌘C (copy)

-

⌃⌥G (focus or bring up the Quick Search tool)

-

⌘V and Return (paste and activate jump action)

In LibreOffice:

- Hold down the necessary modifier key and click on the link.

While activating the link gives a clear advantage to the hyperlink approach, we are still faced with the problem of returning. If we spent the necessary twenty steps to create a round-trip between the two points, then we can use that, but if not we are either faced with creating a temporary bookmark before clicking the link, or manually scrolling back to wherever we came from. So in a sense we can see that although the activation event is, in and of itself, more efficient, the burden of the full action is more so deferred, and arguably not too much more efficient as a net process.

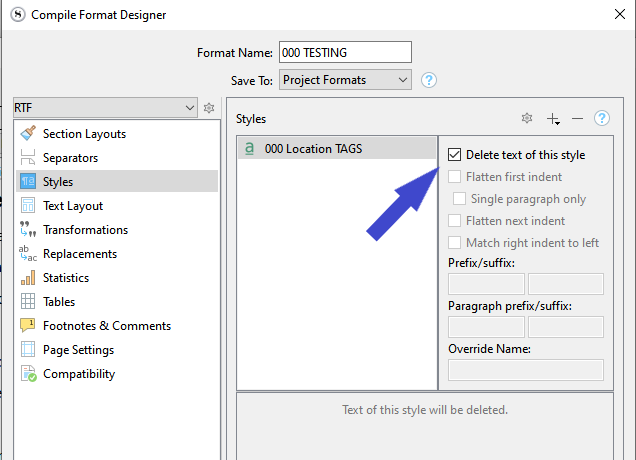

Link Cleanup

It is unlikely that any of these kinds of links are the sort you want ending up in the output your readers will see. In traditional models the tools for linking or cross-referencing are really designed for creating reader tools in the end, and so by co-opting them for internal editorial purposes, we must go through and clean them all out once they have outlived their utility. I won’t bother to go through all of the various steps necessary to do so, or what one would have to do if they were also using these tools to create actual reader tools as well as tools for yourself. Suffice to say I’m fairly sure the process would involve manual labour at all points, removing in a one-by-one fashion the bookmarks and links pointing to them.

With Scrivener, since the links are all marked as “offline content” to begin with, we really don’t need to do anything at all. We could just compile and they will all be gone. If we were determined to clean them out, then we would see a similar level of manual labour. But the key point is that we don’t have to. We can, if we want, but there is no strong need to ever remove them. It could even be argued that leaving these kinds of markers around for future edits is very beneficial, as it establishes a network of relationships that could be of use to us when editing. A revision to text around a marker would incite us to look up that marker, and make sure all related text throughout the work is written in such a way to not conflict with the edit. We’ve already done the hard work in the past of identifying potential points of conflict!

That would be a useful tool in a standard linking model as well—but again you can’t have that, because then your reader is seeing all of those markings as well.

Direction-less Linking

I referred to this before, but to touch on it briefly: this is another content-creation biased capability that you don’t see much of in the traditional model, and that is anticipating that you may at some point need to link to or from this spot, without yet knowing whether you will.

With a marker based system you simply drop the marker down and jot down why. You can throw this into a Project Note in the inspector sidebar, and gradually build a list of these “loose threads” you are concerned about, as you write.

If and when you come across a spot that relates to that concern, you have the marker readily available in the sidebar. You might choose to remove it at that point, since now it is an established “cluster” (of two), or you might leave it around and choose to review your text and make sure this concern is well mapped.

In all cases we aren’t working about directionality. Our declaration of concern is made identically in all places, and can build from none to many without much effort.

And search results “of none” for this marker can be a useful editing tool in and of itself too. Knowing that you had a concern at some point, and seeing that you never followed up on it can be a reason to do some revision. Coming across an anchor point on the other hand doesn’t tell us much. That it was never linked to isn’t something the software can easily tell us.

I use that form of information quite frequently as a form of to-do listing. The to-do itself is a document somewhere with the marker created in anticipation, and I then go and place these markers into the text so that when the trigger happens—when that to-do becomes relevant, I know exactly where to go in the text. As I do so, I delete the markers from the “end points” until I end up with zero search results: that’s how I know I’m done.

There is probably more, and surely there are advantages to hyperlinks that I’m not talking about here as much. I wouldn’t want to leave off with the notion that I’m blind to what links can do, and that in some ways links can do some of the above, more or less. I just wanted to, as I put at the top, shift the conversation purely from a “Scrivener is broken and needs workarounds” stance to something more along the lines of: hey, let’s discuss what it’s doing well that focusses on the sort of things writers need to do in their text, that traditional linking struggles to provide as cleanly or efficiently.